Things to Consider for a Surgery

The idea of having a surgery on your brain can be overwhelming. As a surgeon, I know you have options. Please read the details below about the goals and options that surgeons usually approach.

Should You Have a Surgery?

Defining the goals of surgery is a critical component in the surgery decision-making process because such goals ultimately have to be balanced with any potential neurological morbidity. Tumor location is another important factor to consider because language and motor areas could provide significant limitations towards the goal of safe maximum resection. In such instances, functional preservation is paramount, which implies that a subtotal resection would be acceptable.

In other instances, surgery is intended strictly for the purpose of tissue diagnosis as opposed to resection. Such patients would be subjected to either a stereotactic needle biopsy or an open craniotomy biopsy depending on tumor location and risk, as well as the pretest probability of a successful diagnostic yield based on radiographic characteristics of the tumor.

Biopsies

Biopsies are sometimes the best approach for tumors that are in difficult-to-reach areas of the brain. We can perform very precise biopsies using image-guided stereotactic approaches.

Innovative Approaches for Brain Surgery

A major priority of my surgical approach with brain tumors is to enhance neurological outcomes for brain tumor patients. In order to accomplish this objective, I have incorporated MRI-guided imaging approaches that permit intraoperative interrogation of both tumor and critical white matter fiber tracts in patients undergoing brain surgery. I employ diffusion tractography imaging (DTI), which uses the diffusion of water molecules within white matter fibers in the brain as a surrogate for the orientation and localization of those fibers. Hence DTI permits delineation of critical white matter fiber tracts that are closely associated with the tumor.

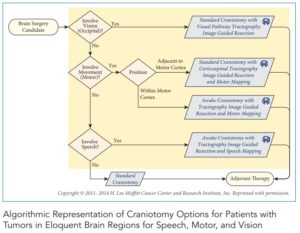

For instance, here is a method that surgeon’s use to decide how to conduct an operation and how they can get the most of the tumor out as possible. This chart is an example of how surgeons review options for any patient with tumors in the region near the brain’s speech, motor, and vision abilities:

The ability to localize and spare critical fibers during tumor resection undoubtedly enhances neurological outcomes. In addition, I employ awake-brain tumor surgeries strategies for functional interrogation during tumor resection. All of these are accomplished through stereotactic techniques that permit navigation during tumor resection.

I take brain eloquence into consideration when deciding stereotactic craniotomy options for brain tumors. Tumors in areas that are eloquent for speech, motor, and visual pathways (temporal/occipital) are surgically treated distinctly from tumors in non-eloquent regions. The risk of neurological deficits is quite profound in eloquent regions, and the deficits themselves can be very disabling for patients. Tumors in non-eloquent brain regions are treated with using a standard stereotactic craniotomy. The stereotactic component permits a safe and reliable approach to the tumor for resection using trajectories that minimize cortical damage.

When patients harbor tumors in eloquent regions of the brain, DTI is often incorporated into the stereotactic craniotomy technique, thereby permitting simultaneous interrogation of tumor and closely associated critical white matter fibers. For tumors close to the visual pathways within the temporal and occipital lobes, I often delineate Meyer’s visual fibers (temporal) and optic radiations (occipital), and stereotactically ascertain their positional relationship to the tumor.

A surgical trajectory to the tumor that spares the visual fibers is then planned. This is particularly important for occipital lobe lesions whereby compromise of visual fibers could result to dense visual field defects. Similarly, for tumors that are close to the motor cortex but do not actually involve motor fibers, I would often incorporate DTI for corticospinal motor fibers into the stereotactic craniotomy technique, thereby permitting simultaneous interrogation of the relation of tumor with motor fibers. In addition, a motor functional MRI (fMRI) is also incorporated to delineate the motor cortex.

What is an Awake Surgery?

When patients present with tumors that involve the motor cortex or speech areas of the dominant frontal and temporal lobes, intra-operative correlation with function is critical. I would always therefore perform an awake-craniotomy that stereotactically incorporates DTI tractography and fMRI.

The awake-surgery permits intraoperative mapping or direct correlation of function to brain anatomy, thereby delineating what can be safely resected. In addition, potential neurological deficits can be identified early since the patient is awake, thereby minimizing the chances of irreversible damage.

The synergy of image-guided co-localization and interrogation of tumor and critical white matter fibers, coupled with the functional advantage of the awake-patient during surgery, significantly improves the outcomes of surgeries in eloquent areas, as has been realized in our brain tumor program.

The Goal of a Surgeon

In summary, surgery has a central role in the management of brain tumors. The goals of surgery should always prioritize neurological functional preservation. Tumor location is critical and can correlate with surgical morbidity. Stereotactic techniques that permit co-localization of critical eloquent fibers in relation to tumor can minimize neurological deficits. Awake-brain surgery permits safe resection of tumors in brain areas that are eloquent to motor and speech functions.